Victory Day (বিজয় দিবস – Bijoy Dibos), 16th December 1971

Victory Day (বিজয় দিবস – Bijoy Dibos), 16th December 1971, Declaration of Independence, March 26, 1971

Victory Day (বিজয় দিবস – Bijoy Dibos): is a national holiday in Bangladesh celebrated on December 16 to commemorate the victory of the Allied forces High Command over the Pakistani forces in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. The Commanding officer of the Pakistani Forces General AAK Niazi surrendered his forces to the Allied forces commander Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora, which marked ending the 9 month-long[1] Bangladesh Liberation War and 1971 Bangladesh genocide and officially secession of East Pakistan into Bangladesh.

Victory Day (বিজয় দিবস – Bijoy Dibos): is a national holiday in Bangladesh celebrated on December 16 to commemorate the victory of the Allied forces High Command over the Pakistani forces in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. The Commanding officer of the Pakistani Forces General AAK Niazi surrendered his forces to the Allied forces commander Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora, which marked ending the 9 month-long[1] Bangladesh Liberation War and 1971 Bangladesh genocide and officially secession of East Pakistan into Bangladesh.

History: The Bangladesh Liberation War (Bengali: মুক্তিযুদ্ধ Muktijuddho) was a South Asian war of independence in 1971 which established the sovereign nation of Bangladesh. The war pitted East Pakistan and India against West Pakistan, and lasted over a duration of nine months. It witnessed large-scale atrocities, the exodus of 10 million refugees and the displacement of 30 million people.

The war broke out on 26 March 1971, when the Pakistan Army launched a military operation called Operation Searchlight against Bengali civilians, students, intelligentsia and armed personnel, who were demanding that the Pakistani military junta accept the results of the 1970 first democratic elections of Pakistan, which were won by an eastern party, or to allow separation between East and West Pakistan. Bengali politicians and army officers announced the declaration of Bangladesh’s independence in response to Operation Searchlight. Bengali military, paramilitary and civilians formed the Mukti Bahini (Bengali: মুক্তি বাহিনী “Liberation Army”), which engaged in guerrilla warfare against Pakistani forces. The Pakistan Army, in collusion with religious extremist militias (the Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams), engaged in the systematic genocide and atrocities of Bengali civilians, particularly nationalists, intellectuals, youth and religious minorities Neighboring India provided economic, military and diplomatic support to Bengali nationalists, and the Bangladesh government-in-exile was set up in Calcutta.

India entered the war on 3 December 1971, after Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on northern India. Overwhelmed by two war fronts, Pakistani defenses soon collapsed. On 16 December, the Allied Forces of Bangladesh and India defeated Pakistan in the east. The subsequent surrender resulted in the largest number of prisoners-of-war since World War II.

Recognition of Bangladesh: The Surrender of Pakistan Armed Forces marked the end of the Bangladesh Liberation War and the creation of Bangladesh (later reduced to a single word). Most United Nations member nations were quick to recognize Bangladesh within months of its independence.

Celebration: The celebration of Victory Day has taken place since 1972. The Bangladesh Liberation War became a topic of great importance in cinema, literature, history lessons at school, the mass media, and the arts in Bangladesh. The ritual of the celebration gradually obtained a distinctive character with a number of similar elements: Military Parade by Bangladesh Armed Forces at the National Parade Ground, ceremonial meetings, speeches, lectures, receptions and fireworks. Victory Day in Bangladesh is a joyous celebration in which popular culture plays a great role. TV and radio stations broadcast special programs and patriotic songs. The main streets are decorated with national flags. Different political parties and socioeconomic organizations undertake programs to mark the day in a befitting manner, including the paying of respects at Jatiyo Smriti Soudho, the national memorial at Savar near Dhaka.

Background: In August 1947, the Partition of British India gave birth to two new states; a secular state named India and an Islamic state named Pakistan. But Pakistan comprised two geographically and culturally separate areas to the east and the west of India. The western zone was popularly (and for a period of time, also officially) termed West Pakistan and the eastern zone (modern-day Bangladesh) was initially termed East Bengal and later, East Pakistan. Although the population of the two zones was close to equal, political power was concentrated in West Pakistan and it was widely perceived that East Pakistan was being exploited economically, leading to many grievances.

On 25 March 1971, rising political discontent and cultural nationalism in East Pakistan was met by brutal suppressive force from the ruling elite of the West Pakistan establishment in what came to be termed Operation Searchlight.

The violent crackdown by West Pakistan forces led to East Pakistan declaring its independence as the state of Bangladesh and to the start of civil war. The war led to a sea of refugees (estimated at the time to be about 10 million) flooding into the eastern provinces of India. Facing a mounting humanitarian and economic crisis, India started actively aiding and organizing the Bangladeshi resistance army known as the Mukti Bahini.

Political Differences: Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country’s population, political power remained firmly in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the “One Unit” scheme, where all of West Pakistan was considered one province. This was solely to counterbalance the East wing’s votes.

After the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s first prime minister, in 1951, political power began to be devolved to the President of Pakistan, and eventually, the military. The nominal elected chief executive, the Prime Minister, was frequently sacked by the establishment, acting through the President.

East Pakistanis noticed that whenever one of them, such as Khawaja Nazimuddin, Muhammad Ali Bogra, or Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was elected Prime Minister of Pakistan, he were swiftly deposed by the largely West Pakistani establishment. The military dictatorships of Ayub Khan (27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969) and Yahya Khan (25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971), both West Pakistanis, only heightened such feelings.

The situation reached a climax when in 1970 the Awami League, the largest East Pakistani political party, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a landslide victory in the national elections. The party won 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan, and thus a majority of the 313 seats in the National Assembly. This gave the Awami League the constitutional right to form a government. However, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (a Sindhi), the leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, refused to allow Rahman to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Instead, he proposed the idea of having two Prime Ministers, one for each wing. The proposal elicited outrage in the east wing, already chafing under the other constitutional innovation, the “one unit scheme”. Bhutto also refused to accept Rahman’s Six Points. On 3 March 1971, the two leaders of the two wings along with the President General Yahya Khan met in Dhaka to decide the fate of the country. Talks failed. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called for a nationwide strike.

On 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (soon to be the prime minister) delivered a speech at the Racecourse Ground (now called the Suhrawardy Udyan). In this speech he mentioned a further four-point condition to consider the National Assembly Meeting on 25 March:

- The immediate lifting of martial law.

- Immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks.

- An inquiry into the loss of life.

- Immediate transfer of power to the elected representative of the people before the assembly meeting 25 March.

He urged “his people” to turn every house into a fort of resistance. He closed his speech saying, “Our struggle is for our freedom. Our struggle is for our independence.” This speech is considered the main event that inspired the nation to fight for its independence. General Tikka Khan was flown in to Dhaka to become Governor of East Bengal. East-Pakistani judges, including Justice Siddique, refused to swear him in.

Between 10 and 13 March, Pakistan International Airlines cancelled all their international routes to urgently fly “Government Passengers” to Dhaka. These “Government Passengers” were almost all Pakistani soldiers in civilian dress. MV Swat, a ship of the Pakistani Navy, carrying ammunition and soldiers, was harbored in Chittagong Port and the Bengali workers and sailors at the port refused to unload the ship. A unit of East Pakistan Rifles refused to obey commands to fire on Bengali demonstrators, beginning a mutiny of Bengali soldiers.

Operation Searchlight: A planned military pacification carried out by the Pakistan Army — codenamed Operation Searchlight — started on 25 March to curb the Bengali nationalist movement by taking control of the major cities on 26 March, and then eliminating all opposition, political or military, within one month. Before the beginning of the operation, all foreign journalists were systematically deported from East Pakistan.

The main phase of Operation Searchlight ended with the fall of the last major town in Bengali hands in mid-May. The operation also began the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities. These systematic killings served only to enrage the Bengalis, which ultimately resulted in the secession of East Pakistan later in the same year. The international media and reference books in English have published casualty figures which vary greatly, from 5,000–35,000 in Dhaka, and 200,000–3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole.

According to the Asia Times,

At a meeting of the military top brass, Yahya Khan declared: “Kill 3 million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands.” Accordingly, on the night of 25 March, the Pakistani Army launched Operation Searchlight to “crush” Bengali resistance in which Bengali members of military services were disarmed and killed, students and the intelligentsia systematically liquidated and able-bodied Bengali males just picked up and gunned down.

Although the violence focused on the provincial capital, Dhaka, it also affected all parts of East Pakistan. Residential halls of the University of Dhaka were particularly targeted. The only Hindu residential hall — the Jagannath Hall — was destroyed by the Pakistani armed forces, and an estimated 600 to 700 of its residents were murdered. The Pakistani army denies any cold blooded killings at the university, though the Hamood-ur-Rehman commission in Pakistan concluded that overwhelming force was used at the university. This fact and the massacre at Jagannath Hall and nearby student dormitories of Dhaka University are corroborated by a videotape secretly filmed by Prof. Nurul Ullah of the East Pakistan Engineering University, whose residence was directly opposite the student dormitories.

Hindu areas suffered particularly heavy blows. By midnight, Dhaka was burning, especially the Hindu dominated eastern part of the city. Time magazine reported on 2 August 1971, “The Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Pakistani military hatred.”

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested by the Pakistani Army. Yahya Khan appointed Brigadier (later General) Rahimuddin Khan to preside over a special tribunal prosecuting Mujib with multiple charges. The tribunal’s sentence was never made public, but Yahya caused the verdict to be held in abeyance in any case. Other Awami League leaders were arrested as well, while a few fled Dhaka to avoid arrest. The Awami League was banned by General Yahya Khan.

Atrocities: During the war there were widespread killings and other atrocities – including the displacement of civilians in Bangladesh (East Pakistan at the time) and widespread violations of human rights – carried out by the Pakistan Army with support from political and religious militias, beginning with the start of Operation Searchlight on 25 March 1971. Bangladeshi authorities claim that three million people were killed, while the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, an official Pakistan Government investigation, put the figure as low as 26,000 civilian casualties. The international media and reference books in English have also published figures which vary greatly from 200,000 to 3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole. A further eight to ten million people fled the country to seek safety in India.

Large sections of the intellectual community of Bangladesh were murdered, mostly by the Al-Shams and Al-Badr forces, at the instruction of the Pakistani Army. Just 2 days before the surrender, on 14 December 1971, Pakistan Army and Razakar militia (local collaborators) picked up at least 100 physicians, professors, writers and engineers in Dhaka, and murdered them, leaving the dead bodies in a mass grave. There are many mass graves in Bangladesh, and as years pass, more are being discovered (such as one in an old well near a mosque in Dhaka, located in the non-Bengali region of the city, which was discovered in August 1999). The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dhaka to the United States State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dhaka University and other civilians. Numerous women were tortured, raped and killed during the war; the exact numbers are not known and are a subject of debate. Bangladeshi sources cite a figure of 200,000 women raped, giving birth to thousands of war babies. The Pakistan Army also kept numerous Bengali women as sex-slaves inside the Dhaka Cantonment. Most of the girls were captured from Dhaka University and private homes. There was significant sectarian violence not only perpetrated and encouraged by the Pakistani army, but also by Bengali nationalists against non-Bengali minorities, especially Biharis.

On 16 December 2002, the George Washington University’s National Security Archive published a collection of declassified documents, consisting mostly of communications between US embassy officials and United States Information Service centers in Dhaka and India, and officials in Washington DC. These documents show that US officials working in diplomatic institutions within Bangladesh used the terms selective genocide and genocide to describe events they had knowledge of at the time. Genocide is the term that is still used to describe the event in almost every major publication and newspaper in Bangladesh, although elsewhere, particularly in Pakistan, the actual death toll, motives, extent, and destructive impact of the actions of the Pakistani forces are disputed.

Liberation War: March to June

At first resistance was spontaneous and disorganized, and was not expected to be prolonged.[45] But when the Pakistani Army cracked down upon the population, resistance grew. The Mukti Bahini became increasingly active. The Pakistani military sought to quell them, but increasing numbers of Bengali soldiers defected to the underground “Bangladesh army”. These Bengali units slowly merged into the Mukti Bahini and bolstered their weaponry with supplies from India. Pakistan responded by airlifting in two infantry divisions and reorganizing their forces. They also raised paramilitary forces of Razakars, Al-Badrs andAl-Shams (who were mostly members of the Muslim League, the then government party and other Islamist groups), as well as other Bengalis who opposed independence, and Bihari Muslims who had settled during the time of partition.

On 17 April 1971, a provisional government was formed in Meherpur district in western Bangladesh bordering India with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was in prison in Pakistan, as President, Syed Nazrul Islam as Acting President, and Tajuddin Ahmed as Prime Minister. As fighting grew between the army and the Bengali Mukti Bahini an estimated 10 million Bengalis, mainly Hindus, sought refuge in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal.

June – September

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col. M A G Osmani as commander in chief, Lt. Col. Abdur Rab as chief of Army Staff and Group Captain A K Khandker as Deputy Chief of Army Staff and Chief of Air Force. Bangladesh was divided into Eleven Sectors each with a commander chosen from defected officers of the Pakistani army who joined the Mukti Bahini to conduct guerrilla operations and train fighters. Most of their training camps were situated near the border area and were operated with assistance from India. The 10th Sector was directly placed under a Commander in Chief (C-in-C) and included the Naval Commandos and C-in-C’s special force. Three brigades (11 Battalions) were raised for conventional warfare; a large guerrilla force (estimated at 100,000) was trained.

Guerrilla operations, which slackened during the training phase, picked up after August. Economic and military targets in Dhaka were attacked. The major success story was Operation Jackpot, in which naval commandos mined and blew up berthed ships in Chittagong on 16 August 1971. Pakistani reprisals claimed lives of thousands of civilians. The Indian army took over supplying the Mukti Bahini from the BSF. They organised six sectors for supplying the Bangladesh forces.

October – December

Bangladesh conventional forces attacked border outposts. Kamalpur, Belonia and Battle of Boyra are a few examples. 90 out of 370 BOPs fell to Bengali forces. Guerrilla attacks intensified, as did Pakistani and Razakar reprisals on civilian populations. Pakistani forces were reinforced by eight battalions from West Pakistan. The Bangladeshi independence fighters even managed to temporarily capture airstrips at Lalmonirhat and Shalutikar. Both of these were used for flying in supplies and arms from India. Pakistan sent 5 battalions from West Pakistan as reinforcements.

Declaration of Independence: The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971, proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these outrages, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Today Bangladesh is a sovereign and independent country. On Thursday night, West Pakistani armed forces suddenly attacked the police barracks at Razarbagh and the EPR headquarters at Pilkhana in Dhaka. Many innocent and unarmed have been killed in Dhaka city and other places of Bangladesh. Violent clashes between E.P.R. and Police on the one hand and the armed forces of Pakistan on the other, are going on. The Bengalis are fighting the enemy with great courage for an independent Bangladesh. May Allah aid us in our fight for freedom. Joy Bangla.

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Mujib was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 a.m. (as per Radio Pakistan’s news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s declaration reached some students in Chittagong. The message was translated to Bangla by Dr. Manjula Anwar. The students failed to secure permission from higher authorities to broadcast the message from the nearby Agrabad Station of Radio Pakistan. They crossed Kalurghat Bridge into an area controlled by an East Bengal Regiment under Major Ziaur Rahman. Bengali soldiers guarded the station as engineers prepared for transmission. At 19:45 hrs on 27 March 1971, Major Ziaur Rahman broadcast the announcement of the declaration of independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur. On 28 March Major Ziaur Rahman made another announcement, which was as follows:

This is Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendro. I, Major Ziaur Rahman, at the direction of Bangobondhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, hereby declare that the independent People’s Republic of Bangladesh has been established. At his direction, I have taken command as the temporary Head of the Republic. In the name of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, I call upon all Bengalis to rise against the attack by the West Pakistani Army. We shall fight to the last to free our Motherland. By the grace of Allah, victory is ours. Joy Bangla.

The Kalurghat Radio Station’s transmission capability was limited. The message was picked up by a Japanese ship in Bay of Bengal. It was then re-transmitted by Radio Australia and later by the British Broadcasting Corporation. M A Hannan, an Awami League leader from Chittagong, is said to have made the first announcement of the declaration of independence over the radio on 26 March 1971. There is controversy now as to when Major Zia gave his speech. BNP sources maintain that it was 26 March, and there was no message regarding declaration of independence from Mujibur Rahman. Pakistani sources, like Siddiq Salik in Witness to Surrender had written that he heard about Mujibor Rahman’s message on the Radio while Operation Searchlight was going on, and Maj. Gen. Hakeem A. Qureshi in his book The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldier’s Narrative, gives the date of Zia’s speech as 27 March 1971.

26 March 1971 is considered the official Independence Day of Bangladesh, and the name Bangladesh was in effect henceforth. In July 1971, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi openly referred to the former East Pakistan as Bangladesh. Some Pakistani and Indian officials continued to use the name “East Pakistan” until 16 December 1971.

Surrender & Aftermath: On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Army forces located in East Pakistan signed the instrument of surrender. At the time of surrender only a few countries had provided diplomatic recognition to the new nation. Over 90,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian forces making it the largest surrender since World War II. Bangladesh sought admission in the United Nations with most voting in its favor, but China vetoed this as Pakistan was its key ally. The United States, also a key ally of Pakistan, was one of the last nations to accord Bangladesh recognition. To ensure a smooth transition, in 1972 the Simla Agreement was signed between India and Pakistan. The treaty ensured that Pakistan recognized the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani PoWs. India treated all the PoWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925. It released more than 90,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months.

Further, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were also pardoned by India. The accord also gave back more than 13,000 km² of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas; most notably Kargil (which would in turn again be the focal point for a war between the two nations in 1999). This was done as a measure of promoting “lasting peace” and was acknowledged by many observers as a sign of maturity by India. But some in India felt that the treaty had been too lenient to Bhutto, who had pleaded for leniency, arguing that the fragile democracy in Pakistan would crumble if the accord was perceived as being overly harsh by Pakistanis.

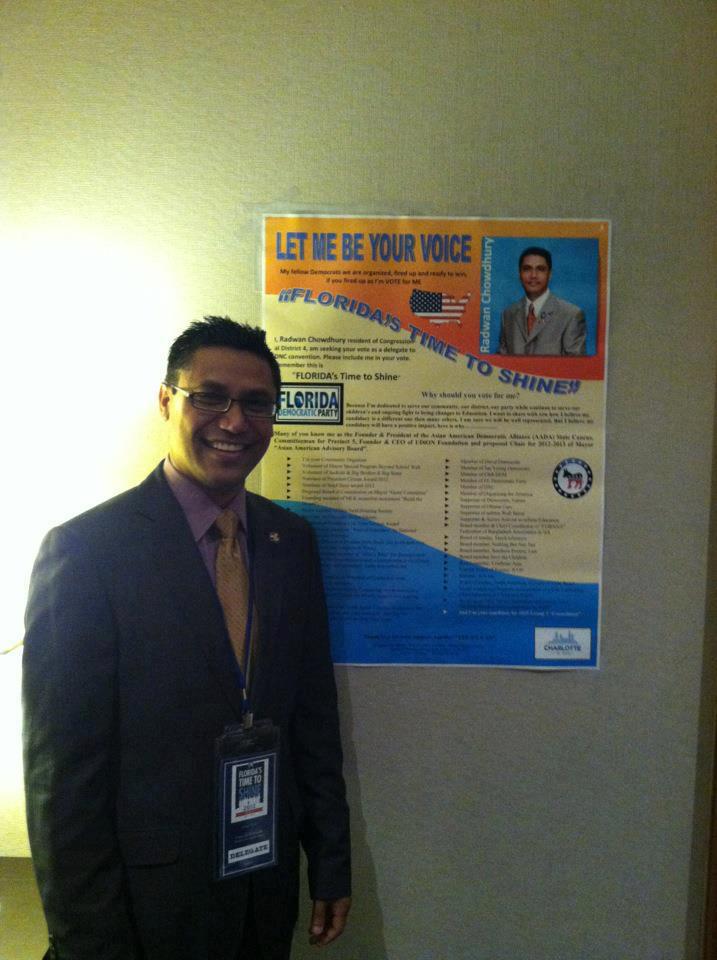

Radwan Chowdhury serves as the CEO of McWeadon Education. He was the founder and CEO of AA Global Solutions, a leading consulting firm and UDiON Foundation a global non-profit organization. Radwan is a motivational speaker, activist, author and an entrepreneur with nearly 15 years of executive management and consulting experience. Radwan believes “Education is the best way to end the cycle of poverty and the exploitation of children”. He’s “Dedicated to the Unfinished Work of Equal Opportunity and Justice for All”.

Radwan Chowdhury serves as the CEO of McWeadon Education. He was the founder and CEO of AA Global Solutions, a leading consulting firm and UDiON Foundation a global non-profit organization. Radwan is a motivational speaker, activist, author and an entrepreneur with nearly 15 years of executive management and consulting experience. Radwan believes “Education is the best way to end the cycle of poverty and the exploitation of children”. He’s “Dedicated to the Unfinished Work of Equal Opportunity and Justice for All”.

No comments